Thanks are due to the late Dr. Michael Persinger for his extensive help.

Persinger’s Endorsement.

The God Helmet ®, part of the Shiva Neural Stimulation System.

Phone:(855) 408-7888

Experimental stimulation of the God Experience [using the God Helmet]: Implications for religious beliefs and the future of the human Species.

Persinger’s Endorsement.

The God Helmet ®, part of the Shiva Neural Stimulation System.

Phone:(855) 408-7888

“Experimental stimulation of the God Experience: Implications for religious beliefs and the future of the human Species.” By Michael Persinger.

Appeared in: NeuroTheology: Brain, Science, Spirituality, Religious Experience, California University Press, 2002, Rhawn Joseph, editor.

NOTE: This article has been re-written on a sentence-by-sentence basis, for easier reading by Todd Murphy. Sections in [brackets] are additions by the editor.

Summary:

We’ve been able to elicit the experience of a “sensed presence” or a “sentient being” in normal people by applying low intensity magnetic fields with embedded complex signals (often called The God Helmet). Our hypothesis to explain these episodes [whether occurring naturally or induced in our laboratory] is that they’re the experience of the part of the human sense of self maintained in left side, perceiving the one in the right side of the brain. They are the mildest example of a “visitor experience” (the perception of a nonphysical being). The experience of God is an extreme example of this phenomenon. Our experimental results and clinical measures support this conclusion. We humans have natural brain functions that allow us to avoid challenges to religious beliefs, which have a lot in common with delusions. Some of the brain activity involved in the God experience [which includes beliefs, adherence to scriptures, as well as the first-hand experience of God’s presence], is also involved with aggression. About 50% of males who had religious experiences, go to church regularly, and are found to have more frequent temporal lobe signs say they would be willing to kill in God’s name, and this could have a strong impact on the future of human beings.

Introduction

One of the fundamental principles in behavioral neuroscience is that all of our experiences are created by, or correlate with, specific kinds of brain activity. [Mental forms follow neural functions.] This activity is controlled by electrical and chemical activities in and between small brain structures, including their. Just as structure determines function, small-scale structures determine small-scale functions.

This principle operates in several ways. The first is that all but a few experiences or perceptions are responses to objective events and stimuli.

The idea that mental forms follow neural functions forces us to see that all religious experiences and states of consciousness, from heightened awareness of the self, to feelings of love and devotion, and the direct perception (or vague sense) of God’s presence, are reflections of activity in the brain. If science can isolate the stimuli that elicits an experience, then it should be possible for any experience, including seeing God (or feeling his presence) to eventually be investigated, verified and reproduced in the laboratory.

In one of our case histories, in 1983, we did a routine EEG study to examine the effects of transcendental meditation™. During this study, an experienced TM instructor showed an electrical anomaly over her right temporal lobe. Simultaneously, during this “electrical seizure,” she said she was “filled with the spirit” and that she felt the presence of God with her. This happened in a laboratory, not a church or temple. The electrical event we saw on her EEG, which lasted about 20 seconds, and happened at the same time as her religious epiphany.

An obvious question appeared. If we could find essential electrical process in the brain that correlates with the experience of God and then elicit the same process or electrical activity in people without them knowing what the stimulation was for, would they experience God? There are many clinical records of patients with complex partial (“temporal lobe”) epilepsy, focused in the limbic system or the temporal lobe on the right side, who also had mystic experiences and contact with God. Of course, many of these patients were reported in the medical literature before the technology to design the experiment existed.

The search for the self leads to the sensed presence

One of the last remaining challenges in neuroscience is to understand the brain’s foundations for the sense of self. Some of its basis seems to be in verbal processes, supported by language centers on the surface of the left side of the brain. The human sense of self is, in part, based on language. People often show themselves willing to fight and die to preserve their culture and their language, especially the specialized vocabulary of their religion [including words like “salvation, “illusion”, “prophet”, or “God”, without which it’s impossible to express religious beliefs]. This looks like a simple extension of the way people identify themselves through the words they use. Without language, the sense of self, as we humans know it, would not exist.

In the late 1980s, our research group was investigating the brain’s role in creativity and insight. Many of the great minds in human history, including scientists and people who founded religious and spiritual traditions, have said that their insights happened along with a feeling of communion with something greater than themselves. The knowledge, information and insights appearing in these moments often went beyond anything that they’d learned or encountered during their lives.

To study this phenomenon, we developed a computer-based technology to apply complex signals, carried by weak magnetic fields, through the brain. The basic procedure involves seating the blindfolded subjects in a completely silent [and vibration-proof] chamber (which is also a Faraday cage). The idea was to imitate the cave-like conditions in which so many “inspirational insights” had appeared to people throughout history. Blocking out vision and hearing from their minds would allow many pathways to respond to the experimental magnetic signals that would usually be busy, monitoring the environment.

Most of our subjects [80%] reported that they sensed a presence, sentient being or “entity” in the chamber with them. The subjects were more likely to report the sensation, and interpret it as a “being” according to three factors. 1) Their temporal lobe sensitivity, as measured using EEG and their responses to a questionnaire. 2) Their beliefs about nonphysical living things. 3) The shape or pattern of the signal embedded in the magnetic fields. The subjects had strong emotional responses to the sensed presence, and they also found the presence to be personally significant, [as though the being they experienced in the laboratory was speaking to them personally, or concerned with their welfare]. The way the subjects remembered these experiences was strongly influenced by the way they explained it within a few seconds of the event.

We work with the hypothesis that the sense of a presence is a “prototype” of the God experience, and that it’s actually a brief moment when the self on the left side of the brain is aware of its counterpart operating out of the right hemisphere. The electrical activity in the left hemisphere of the brain that generates the sense of self experiences the person’s right hemispheric “self” as “the other” when it intrudes into its awareness.

[The Sensed Presence happens when the ‘self’ managed by the left side of the brain becomes aware of the ‘self’ that’s managed on the right side. Neither of them are independent. They each receive contributions from the other, and there are always pathways connecting them. When these pathways don’t have their usual control in place, a person can be aware of their two ‘selves’ at the same time, and the ‘right-sided self’ is projected into the space around them, perceived as an being outside themselves. – Editor]

The “self” on the left side of the brain is the “default” sense of self, which operates in our normal states of consciousness. We identify it as “me” or “myself.” The activity supporting the two selves is normally kept separate, each mostly staying on its own side, but when they intrude on one another, we sense a presence. It usually doesn’t happen very often for most of us, except perhaps when we’re dreaming, but many people should expect them from time to time, given the fact that the hemispheres are “empowered” to inhibit one other. These “intrusions” become more likely during times of personal crises, depression, during meditation, or under the influence of certain drugs.

Because these episodes involve a disproportionate contribution from the right side of the brain, the features, phenomena, and “properties” of the right side of the brain figure prominently in their details. Thus, they can be profoundly emotional, and feel larger-than-life (for instance, seeming to happen on a cosmic scale). In the same way, they can be fraught with profound meaning, and exceed the “boundaries of the self,” and go “beyond words.” Our EEG measures, together with the themes of the experiences, show that they involve the area where the temporal and parietal lobes meet, as well as the amygdala (associated with emotion and cosmic meaning) and the hippocampus, the gateway to memories and inner images. The most common themes and sensations that happen along with the sensed presence sensation include vibrations in the body, dreamlike states, out of body experiences, feeling like one is spinning, as well as fear, anger, or sexual arousal.

In one example, a 21-year-old diabetic woman was given a burst firing signal (from the amygdala), said “I felt a presence behind me and then along the left side. When I tried to focus on its position, the presence moved; every time I tried to sense where it was, it would move around. When it moved to the right side, I experienced a deep sense of security like I have not experienced before. I started to cry when I felt it slowly fading away (we had changed the signal). The task of focusing on the “being’s” position would have changed the electrical activity in her brain. The magnetic signals would have integrated with the mildly different activity in her brain from that task, and the experiences, as well as the way she interpreted them would have changed as well.

Different magnetic signals have produced different sensations [though they aren’t as effective in producing the sensed presence]. For example, a woman who received a different (frequency-modulated) field over the right side where the temporal and parietal lobes meet said that she felt “detached from my body … I am floating up… There is a kind of vibration moving through my sternum… There are lights or faces along the left side. My body is becoming very hot… Tingling sensations in my chest and stomach… Now both arms. There’s something feeling my ovaries. I can feel my left foot jerk. There is someone in the room behind me. The vibrations are very strong now. I can look down and see myself.” [She had an out of body experience, but not a sensed presence.]

We’ve been impressed by the common themes of these experiences, as well as their extensive overlap with the phenomena of specific neurological functions. They’ve been reported by hundreds of university students and other groups (including visiting journalists) during last 15 years as effects from The God Helmet. [This article was published in 2002.] Although older people, artists, musicians, writers, and women in general are more introspective, the themes and phenomena of their reports from specific magnetic signals have been consistent. Nevertheless, each person’s experience is unique, and tends to reflect their beliefs, as well as the names they’ve learned for them. [One person might experience Christ, while another might feel they were in Allah’s presence. Both would feel they were in the presence of a deity. Another might feel that the spirit of a deceased relative was with them, while someone else might feel that there was a nature spirit nearby. Both would feel a spiritual presence. We could say that the form comes from the stimulation, while the content reflects the person’s belief, life experience and private symbolism.]

In another example, a 25-year-old man who received the (frequency-modulated) signal over both sides of their head said: “I felt as if there were a bright white light in front of me. I saw a black spot that became a kind of funnel… No, tunnel; that I felt drawn into… I felt (I was) moving, like spinning forward through it. I began to feel the presence of people, but I couldn’t see them; they were along my sides. They were colorless and grey-looking people I know I were in the chamber, but it was very real …”

Applying these magnetic signals over the right hemisphere in our lab experiments has regularly generated experiences of God or other religious beings in people who believe in them. For example, a 50-year-old man, who said he felt the presence of the Virgin Mary or Christ often in his daily life, volunteered for one of our experiments. Without him knowing how long each signal would be applied, he let us know (by pressing a button) when he had the sudden “feeling” or the actual “visual presence” of Christ on his left side. These happened when a specific signal was applied over the right temporal lobe. That signal imitated a pulse sequence associated with memory creation (long-term potentiation) in hippocampal tissue. Presenting this signal repeatedly produced and obvious (but reversible) normal response. It reduced the amount of alpha activity measured over both occipital lobes and the right parietal area.

Over the years, many people have asked us what atheists experience from God Helmet stimulation. [As of 2002,] We’ve worked with about 20 people who identified themselves as atheists, primarily experts in various sciences who visited our laboratory. They also reported the sensed presence and out of body experiences, but explained them as coming from their own minds, instead of a sacred source separate from themselves. They often compared the experiences to the states of consciousness created by hallucinogenic compounds. These results strongly support the idea that the feeling of a “sentient presence” is within the normal repertoire of experiences generated by the brain, and reflect its architecture and functions, which contribute to our survival. [The emotional and cognitive effects of sensing the presence of a nonphysical being, real or illusory, are part of the human survival strategy, even though not everyone is equally prone to these episodes. In fact, they may provide alternate cognitive styles that allow humans to solve problems and take advantage of opportunities.]

The Experimental Procedure and The God Helmet Technology

Many previous studies on the effects of magnetic neural stimulation have used very simple magnetic fields. In contrast, we believed that the complexity and information content in the magnetic fields was more important than the field strength for our experiments. Studying biochemistry using with two molecules, like hydrogen and water, (because they’re simple and easy to work with), wouldn’t have allowed the special properties of more complex organic chemicals, like nucleic acids or proteins, to be discovered.

We can compare our complicated, irregular low intensity magnetic fields used to influence neurons to the complexity of the spoken word. Suppose you were studying, and a 1000 Hz sine wave was played in the room with you. Most likely, you wouldn’t respond unless it was loud enough to be irritating. However, the complex mix of frequencies that produced the sound of someone saying, “God is here” or “help me” would get your attention even if it was very quiet. The difference is that the sound of the spoken words means something, while the sine wave doesn’t. The information in those words is encoded in asymmetrical complex sound patterns, and the way you heard them, as well as how you explained them, they could have a powerful impact on the way you behave, either in that moment, or for the rest of your life.

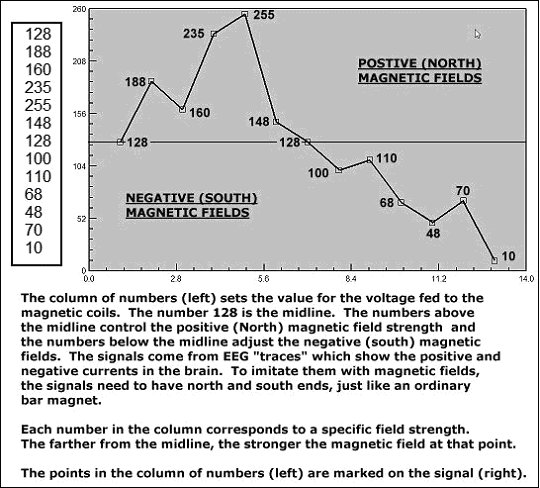

We learned that the signals in our magnetic fields are most effective when they imitate the ones that the brain produces naturally. We derived these signals, magnetic mirror images of the brain’s electrical activity, both from the activity of neurons, singly and in groups, from EEG patterns and measurements. We converted them to columns of numbers, and fed them to a digital to analog converter, which converted the values for the numbers into electrical current. Each number corresponds to a specific voltage, and the fluctuating electrical current was fed to magnetic coils attached to a person’s head, which produce magnetic fields that also fluctuated in the same pattern.

To avoid any direct current induction from them, and to prevent physical vibrations, the magnetic coils never touch the person’s scalp. Instead, the coils were built into a helmet so they were located over the temporal lobes, including the region where the temporal and parietal lobes meet. We also used an alternative hardware arrangement, where the coils were placed in containers that could be located over any part of the brain and held in place with Velcro. The eight coils are placed above the scalp just above the ears, with four coils on each side of the head. These were designed so that the headsets could produce magnetic fields that ran through the brain from one side to the other, or could be rotated around the head.

There are four major design features in the God Helmet’s magnetic signals. 1) The shape of the individual signal. The changing values in a column of numbers (a data file) change the strength of the magnetic field. If the signal is displayed on a graph, the farther a number is from the midline, the stronger the magnetic field strength. 2) The length of time each number in the data file is “played.” This sets the length of time the magnetic signal is produced by each coil. In both humans and rats, the most effective “point duration” is between one and three milliseconds. 3) The length of time between each “run” of a signal. For example, our burst firing signal, designed using an EEG pattern from the amygdala (first seen in epilepsy, and later also found in normal people) seems to have its greatest effects when delivered once every four seconds for about 20 minutes. In rats, it was seen to result in analgesia equivalent to 4 mg per kilo of morphine. Presenting this signal continuously, without the four second gap (a “latency”) between each run, didn’t have the same effect.

The fourth God Helmet design feature is how long the stimulation using a single magnetic signal is used. Most of our experiments have been confined to stimulations lasting between five and 40 minutes. This helped us develop further research strategies and to investigate potential clinical applications, [as well as to elicit altered state experiences]. Although repeating the same pattern can elicit simple sensations within about two minutes, presenting a sequence of different signals (for 2 to 5) minutes each appears to be sufficient for their effects to be seen on EEG, and to elicit more complex sensations. [In most “God helmet” stimulation sessions, two signals are used, for not less than 20 minutes each.]

We use three different methods to measure the experiences associated with our magnetic signals. First, we record what the subject says during the stimulation. These reports come immediately, in real-time, and consist of the subjects own words, which we can analyze later on for their emotional meaning. One disadvantage of this method is that talking too much can interfere with the experiences. [Talking excites language centers, located on the left side of the brain, while many experiences rely on predominantly right hemispheric functions. Too much of one can interfere with the other. For example, when people come out of a trance or meditation, they often need a few minutes to collect their thoughts and begin to talk again.]

Our second technique has been to ask the subject’s questions after the stimulation session is over, following a questionnaire. They’re asked to rank how often they felt typical sensations felt or underwent specific experiences. This technique doesn’t require the subject to talk during the stimulation, which would compete for their attention as the phenomena happens in real time. One disadvantage of this technique is that, like dreams, the experiences can be forgotten quickly if they aren’t recalled soon after they occur. Moreover, the content of the questions can influence a person’s memory of the actual experience. [For this reason, the questions are kept as neutral as possible, and a placebo field is used in the experiments.]

Another technique we used to gather the “sensed presence” data is to tell the subject to press a button on their left when they feel the presence on their left side, and to press another button on the right when they feel it on their right. In this way, we can record the exact time the sensation occurred, and look at their EEG recording from the same instant. The subject doesn’t have to disrupt the “flow” of their experiences by talking about them. Recording the button presses, and comparing them to EEG allows us to apply several different signals and see which one was most effective in producing the sensed presence for that individual. One disadvantage of this method is that it leads the subjects to expect the sensed presence, and may make it difficult for them to pay attention to other experiences and sensations. This limitation meant that the button press method could not be used in all of our experiments. [Even though this procedure tends to create expectations, we can still use placebo (“sham field”) controlled conditions, where neither the experimenter nor the subject knew if they were receiving the stimulation or not. Our intake procedure included informing the subjects that they may or may not receive magnetic field stimulation, introducing a tendency for them to be a bit doubtful.]

Neither the subjects nor the laboratory technician (usually a graduate student or senior undergraduate student) applying the stimulation knew the hypothesis for the specific experiment. The subjects were told that it was concerned with relaxation (a “misdirection”) and that weak magnetic fields may or may not be applied at some point during the procedure.

The location for the coils is another important point in the stimulation’s design. [Placing the coils over the temporal lobes was found to be more effective for producing the sensed presence, stronger apparitions, and even the experience of God, than any other cerebral location.]

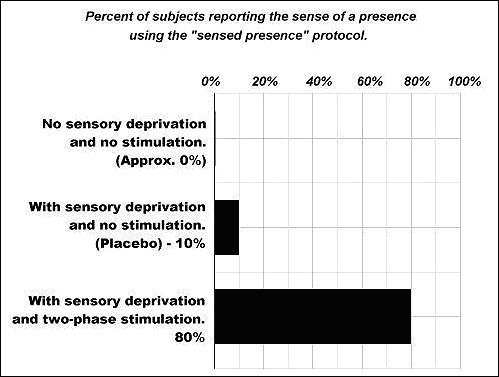

Several of our experiments, involving around 100 subjects [as of 2002], made it clear that the most effective procedure for inducing the sense of a presence is a two-phased stimulation session. The first phase applies a frequency modulated signal so it “loops” without a break, to only the right temporal lobe for 15 [or 20] minutes. In the second phase, we apply the burst-firing signal to the temporal lobes on both sides (once every three or four seconds) for the same length of time. If the feeling of a presence appears in the first phase, it feels as though it’s on the subjects left side, and tends to feel more apprehensive or anxious. If it appears in the second phase, the “being” feels like it’s on either the right side or both sides, and it’s most often pleasant, even spiritually uplifting. About 80% of our subjects who receive this two phased session report that they felt a presence. There were a lot fewer reports of the sensed presence when we applied the same stimulation in the opposite order. In most of our experiments, only about 10% of the people exposed to the placebo condition [applied in complete darkness and absolute silence] felt the sense of a presence. Most of these subjects also had more frequent temporal lobe experiences [such as déjà vu, the sense of a presence, tingling sensations, and illusory feelings of movement] in their daily lives than normal, (measured with a questionnaire that asked about these “temporal lobe signs”). [We should take note that sensory deprivation provides a context for several types of altered state experiences, making it unlikely that control subjects, receiving placebo (zero strength) magnetic fields in our sensory deprivation chamber would report nothing at all. The critical point is not whether control subjects had anything to report, but rather the difference between subjects and controls.]

The “shape” or “profile” (also called the “pattern”) of the signal appears to be the most important feature for eliciting the sensed presence. [Other signals are more likely to elicit other phenomena, such as the frequency modulated (“chirp”) signal, which has generated many reports of seeing an “infinite space,” and out of body experiences, phenomena which occur much less often with the burst firing pattern. [Another signal, derived from activity in the hippocampus while memories are being formed, doesn’t produce the sensed presence experience very often, but it does create a strong sense of pleasantness, when it’s applied over the right side. In contrast, the burst firing signal is associated with negative feelings over the right hemisphere and positive feelings over the left.]

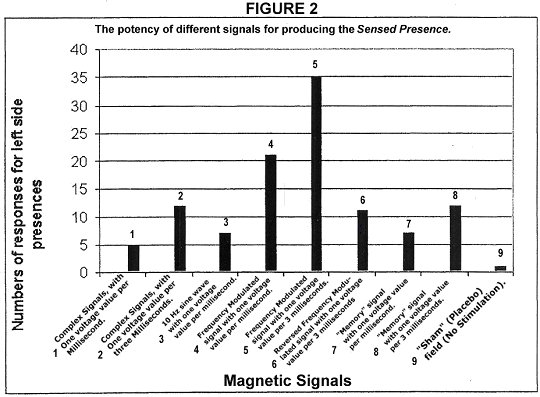

This graph (Figure 2) shows how some signals are much more effective than others for producing the sense of a presence on the left side of the person. The amygdala burst-firing signal (not shown) is the most effective overall. The placebo (no field) was the least effective.

Figure 2 shows the results of exposing approximately 100 subjects to a number of different signals, applied at different speeds. The most effective configuration in this group (which doesn’t include the burst firing signal) was the frequency modulated (“chirp”) signal, when it was applied with 3 milliseconds for each voltage value (“pixel”) in its column of numbers. When the signal was “played backwards,” it lost about two thirds of its effectiveness. Even a complex group of signals, with 40 different shapes, wasn’t as effective. [Simply making the signals more complex doesn’t make them more effective. It’s much more important that the magnetic signal integrates with the brain’s own electrical signals, making its “shape” more important than the strength of the field that carries it.]

Experiences outside the Laboratory

We’ve gathered data from questionnaires of temporal lobe experiences filled out by 1,500 students over 15 years. We’ve found that the spontaneous experience of the sensed presence in daily life tends to happen for people who have other, similar experiences. There also more likely to have mystic experiences such as “being visited late at night by a cosmic consciousness” or moments of being “at one with the universe.” [This phrase can refer to several different experiences and states of consciousness]. We have called the source of both kinds of altered state experiences the “Muse” factor. Other such spiritual experiences include feeling “intense meaning from reading poetry and (spiritual or romantic) prose” or feeling that one’s thoughts are so important that they have to be written down. Other examples include vestibular sensations and experiences of low-frequency waves running through one’s body in twilight sleep, or “hearing one’s name called just before falling asleep.”

As part of our work both with normal people and brain injury patients, we’ve collected information from more than 500 patients who had been through traumatic injuries. Most of these didn’t lose consciousness, or exhibit any verified brain injuries. More than half of these patients told us that they began to feel a sensed presence soon after the injury. In every case, these patients also felt that they were no longer the same person they were before their head trauma.

These experiences were so powerful and unpleasant that most of the patients hadn’t told their doctors or family members about them because they were afraid they’d be called “crazy.” In general, if the presence appeared on the left side most often, the experience was unpleasant. These patients often had anxiety attacks and feelings of apprehensiveness appearing along with the sensed presence experience. If the presence mostly appeared mostly on the patient’s right side, the experience was either neutral or positive. In these cases, the patients frequently mentioned that they received “inner” messages, which they interpreted as perceiving the thoughts of the “being” or simply “just knowing” things, [without always knowing where the information was coming from].

The negative presences were most commonly interpreted as ghosts, demons devils, or other malevolent beings, cultural icons that represent evil.. In contrast, positive experiences were explained as the presence of deceased loved ones, like spouses, parents, angels, or God. They were believed to be “good” beings. These “angelic” beings often reduced the person’s anxiety.

We also found the sense presence happens more often between midnight and 6am, especially between 2 and 4 AM (local time). This peak is also the time of day when temporal lobe seizures are most common. We saw this in our patients as well as reports from in the 19th century, before effective antiepileptic medications had been developed.

Because these are essentially electrical events in the brain, it comes as no surprise that, when the earth’s magnetic field becomes more active, there’s an increase in “apparitions” and ”visitor” experiences (visual sensed presences), as well as the kind of epileptic seizures that begin in the limbic system. To test this in one of our studies, we did an experiment where we produced seizures in epileptic lab rats by applying a magnetic field carrying signals that commonly appear during geomagnetic storms.

Geomagnetic activity can encourage electrical sensitivity in the limbic system. When geomagnetic activity reaches higher levels (above 20 nanotesla), the amount of melatonin goes down. Melatonin can mute electrical activity in the hippocampus, a structure that’s heavily implicated in dream imagery. Reducing nighttime melatonin levels, especially in the hippocampus, can increase the chances for spontaneous altered state experiences at night. We’ve been able to lower melatonin levels in rats by applying magnetic signals (somewhat stronger than that) at night, when melatonin levels would ordinarily be increasing.

Personality changes and God experiences

A first-hand experience of God can create changes in the temporal lobes and the limbic system, which are particularly sensitive to these changes, and these changes invariably alter people’s personalities. Whenever the limbic system undergoes changes, so does personality. New synapses often form in specific areas of the hippocampus (and the tissues that surround it), and this can have a strong influence on the way we think. These new synapses even contribute to seizures in people with temporal lobe epilepsy. [Similar changes in the amygdala alter people’s emotions, making them prone to bursts of anxiety or joy, and changing their default emotional responses (“affective style”).

Some parts of the hippocampus [which is involved in inner imagery of any kind, including memories and dreams, as well as meditation and trance] are extremely sensitive to brief chemical and physical traumas. One of them has very strong responses to reduced oxygen, high stress levels, or reduced blood supply. The hippocampus also has an unusual layout for its veins and arteries that makes it more vulnerable to blockages than other parts of the brain. Geriatric patients show EEG signs of [faint] seizure activity in the temporal lobes more often than others, so we can understand why older people tend to report more religious and spiritual experiences.

Sudden and unexpected brain trauma, [like concussions] can also alter the brain, and create personality changes. Near-death experiences, which can happen when a dying person’s limbic system lacks enough oxygen or glucose, are often followed by [dramatic] personality changes. Such people can find themselves emphasizing the spiritual side of their lives. They often say that they’ve lost their fear of death and any anxiety about the purpose of their life.

Two researchers, Bear and Fedio, have described the personality changes that appear in people with temporal lobe epilepsy. Other researchers have described how these patients maintained their intelligence and ability to interact with people, in spite of their seizures. They often talked about their powerful mystic experiences, many with striking visual hallucinations, as well as their profound beliefs.

Those who’ve had brain injuries that affected the temporal lobes have a great deal in common with those who have spiritual experiences and some temporal lobe epilepsy patients. Other researchers have found that a “God experience” [in both epilepsy and in the lives of the saints] often involves powerful dreamlike episodes, strong feelings of movement, like being “uplifted”, or the sensation that “a burden” has been removed. Such mystic experiences can also include the sensation of “sudden knowing,” or hearing messages from higher beings, and the feeling that their revelations are very important for them (“intense personal meaningfulness”).

A person can find they are confused and disoriented when a mystic experience is over. They may feel that they have lost some time, show a partial amnesia, and they may weave some of the thoughts and feelings that come after the episode into their memory of it. They can be very selective about who they confide in, but still seek out people [such as a priest, another mystic, or a spiritual teacher] they can talk to about it. One of the most common explanations for these experiences is that the person was “called by God.” The specific name for God, of course, as well as ”his” attributes, and the religious teachings it conveys vary from one culture to the next. [A Hindu spiritual guide might advise that the person take on meditation practices or spiritual disciplines that discourage anger, fear, or desires. In contrast, Catholic teachers might advise prayer, taking the sacraments and service to the poor. Evangelical Christians would encourage fellowship, Bible study, prayer, “witnessing” and baptism].

In the end, personality changes almost invariably follow mystic experiences, which like seizures, “edit” pathways in the limbic system and the temporal lobes [”pruning” away inhibitory synapses], making them less stable. [These changes are often interpreted as “being touched by God,” being “awakened” or as “opening” to one’s “true self”. Dramatic neural events, like seizures, head injuries, and near-death experiences make changes in the brain primarily by overwhelming inhibitory synapses, and causing them to “drop out” more than excitatory synapses. The language of mysticism often speaks of spiritual growth, whether through slow and steady progress or through sudden epiphanies, very often refers to achieving “higher states” of meditation or communion with God as a loss of inhibitions. A person’s self-importance is disinhibited when they “get out of their own way”. Someone might become closer to God, and feel that they have “stopped resisting.” Meditation progress is seen as losing the inhibitions to awareness, focus, and relaxation. Active mystics strive to lose their inhibitions against the object of their quest, whether it’s the self within, or the divine without. The language of neuroscience and the language of mysticism agree. Our own inhibitions repressing surrender to God or perception of the “true self” are the primary obstacle mystic progress, according to many mystic traditions.] There can be moments of automatic behavior. The sense of self seems to widen so that they “connect with more of the world around them have an impact on their senses and emotions. The person may begin to feel that what they’re going through, in both their life experiences and moment to moment, is happening because they were “selected” for one of “God’s missions on earth” [or that their destiny, selected by their karma, is coming to fruition]. A trait called “viscosity” [”resistance to change in flow”] may appear, where the person may seem to be “stuck” on specific ideas or even just phrases. They may begin to see meaningful patterns in unrelated events, as their emotional life becomes wider [as their “minds and hearts open”]. They may also rely on their intuition instead of reason or concrete facts. Such people are also likely to focus on philosophical, metaphysical, or religious ideas, and can find themselves compelled to record their thoughts and feelings [in journals, diaries, or blogs, acting out a trait called “hypergraphia”].

In addition, the person, feeling that they have a “cosmic mission,” may be driven to proselytize, “spread the word” or “share their vision” with others. Their social circle changes as they become drawn to people who share their beliefs, aspirations, and “vision.” The person is now “different”, “reborn,” “awakened,” or feels that they have been given a new “path.” Even though these changes may reshape their personality, they still interact with others normally and retain their intelligence.

Historical Examples

Many religions have evolved around individuals with biographies that strongly suggest they went through powerful enhancements of their temporal lobe’s functions. Their mystic experiences happened in caves (Mohammed) [صَلَّى اللّٰهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ], during social isolation in the wilderness (Christ), or in the sensory deprivation meditation provides (The Buddha). Each of them was convinced that they had found the spiritual character of the universe they lived in, and each began religious traditions that influenced the development of later civilizations.

In the 15th century, Guru Nanak, a musician who was out of work at the time, went for his daily bath in a nearby river and then disappeared for about three days. When he came back, he kept silent for a day and then said, “There is neither Hindu nor Muslim. I will follow God’s path.” The Sikh religion grew out of his revelations. Today, skeptics might see a similar case as being not unlike an “alien abduction” experience.

In the 19th century, a young man, the son of a minister was walking in the forest where he felt a presence. He began to receive information from a “being,” which stayed with him persistently. He felt compelled to record these inspirations from [ Moroni ], a “messenger of God”. [Other revelations followed, including the discovery of a Scripture inscribed on gold plates, which the same angel helped him to translate.] This was the beginning of the Mormon Church of Latter Day Saints.

The experience of God offers some of the most profound feelings human beings can experience. Dostoyevsky wrote about his seizural epiphanies, saying, “The air was filled with a big noise and I thought it had engulfed me. I have really touched God. He came into me, myself; yes, God exists. I cried and I don’t remember anything else. All of you healthy people can’t imagine the happiness we epileptics field during the seconds before our attacks. I don’t know if this felicity lasts for seconds, hours, or months, but believe me, for all the joys that life brings, I would not exchange this one.”

[The editor’s book: “Sacred Pathways: The Brain’s Role in Religious and Mystic Experiences” has a chapter on the subject that examines stories from several other mystics. These include Thomas Merton, Adm. Byrd, R. Buckminster Fuller, St. Seraphim of Sarov, Ramana Maharishi, Eckhart Tolle, Osho, Malcolm X, St. John of the Cross, Bill W., (one of the founders of Alcoholics Anonymous), and several others. Interested readers can find it on Amazon.com]

However, these experiences aren’t always harmless. In one 19th century case, a temporal lobe epileptic told his doctor: “God told me that in my next life I would be born (with the initials) C.H.S. I would marry my last sweetheart, be a millionaire, and that I would be (a) strong, hopeful, and powerful Christian millionaire. I feel God’s voice in my left ear at night. I feel the Lord in my chest. I see stars in my eyes. I have seen Christ crucified. God told me I would never have any more fits. God told me to bite off a patient’s ear. If God told me to do wrong it feels as if I would do it.” [Another, possibly more telling case, is that of Roch Thériault, a Canadian cult leader who showed several signs of temporal lobe sensitivity (including religious conversions, and personal revelations from God). He founded a cult where members were even brutal punishments for minor failings, and eventually came to be regarded as one of the worst criminals in Canada ’s history.]

Belief in God as a ‘cognitive virus’

Cultures have been defined as communities of people who share expectations. These beliefs make the world we experience seem understandable. They allow us to make predictions about the future and to reduce our fear of the unknown, with its anticipation of terror and deep fears of things we often can’t imagine.

Even though we’re conditioned to suppress it, perhaps the one thought that’s most responsible for maintaining belief in God is the simple sentence “I will die”. Although our species has devised three ways to defuse this linguistic time-bomb, it goes off when we think that our demise is immediate and inescapable.

The first and most common way we avoid the thought that we’re going to die is to remove the expectation that we’ll cease to exist when it happens. Every human society or religion has a word or idea that alludes to infinity, omnipresence, and eternity, and to some extent, imposes these qualities on human beings, even if only in special circumstances. If something is eternal, it cannot end. If we never end, then there is no need to be anxious about death.

Two accomplish this; humans have come to see ourselves as part of the “infinite.” Sayings like “I will have eternal life because I have faith in God” or “I will live on with God,” “life everlasting” or “I will soon be reborn” effectively reduce anxiety, if we believe that God or consciousness is eternal. The “self” never dies, because it endures forever [having always been a part of the divine].

The idea the self is more than the body may derive from the simple observation that one’s mind and body can behave separately, as they do while we’re asleep. From the outside, the body may not move at all, while we’re inwardly occupied with our dreams. This division of mind and body encourages the concept of the soul, which, like our minds while we’re having dreams, appears to exist independently of our bodies, [and death looks like “falling asleep.”].

Belief in God can’t be refuted and can never be tested. God is always believed to be “nonphysical,” and beyond all measurement. Invoking God and “his” will provides a “last resort” for questions that can’t be answered any other way. Faith, a religious idea that implies strong belief [or the “feeling” that something is true], is itself used to prove the validity of belief in God. When challenged, religious believers often demand that the challenger should prove that God doesn’t exist.

Science can’t prove a negative, but, this limit isn’t a weakness in scientific method. We can also think of it as encouragement for scientists to consider unending possibilities, so long as measurement is can be attempted. The existence of God can’t be refuted, and scientific method can’t prove that “He” doesn’t exist. No one could believe that the universe is governed by invisible, nonmaterial pink elephants, but no one can prove that they aren’t there.

Another way of resolving the mental dilemma of one’s own death has been to deny the existence of the self that will one day die. Several Eastern religions teach that the “self” is an illusion, supported by our use of language and the beliefs of our cultures. In this way, the “path to truth” is to suppress language [quieting the “monkey mind”], and focusing on what remains when words are replaced by silence. Another belief, inspired by Eastern religions, is that the self is only a part of a larger “cosmic whole,” which has no end in time or in space [“Atman is Brahman”].

The third way to defeat the thought that “I will die,” is to replace the word “will” with a word in the present tense, like “I am dying,” [“he who was not busy being born is busy dying.”] Because this way of thinking about death involves translating it to the present, there’s no reason to fear the future. It always already exists in the present moment. The discomfort of the present moment doesn’t include the fear and anxiety that appears when we expect a threat in the future. [“O death, where is thy sting?”].

We can see that belief in God and religion offered us survival advantages, during our evolutionary history. If they hadn’t helped us to survive, these behaviors would have been “pruned” out of the repertoire of common human activities a long time ago. If they were bad for our survival, they would have been deleted from the human genome. [In addition, we should remember that religious beliefs encompass much more than just belief in God. Religious beliefs contain guidance, however useful or useless, for many types of human behavior. Although religious morality can become oppressive in square bracket especially after it was codified in Scriptures]. At one time it may have been a repository for a wide range of beneficial commands and suggestions, which pushed our behavior towards adaptivity. Religious injunctions to avoid killing or harming members of your own community, as well as respect for their possessions, would have once helped human beings live together, especially in our early, tribal, evolutionary history. Commandments that demand that we don’t interfere with other people’s romantic and sexual relationships could easily help avoid conflicts between people, with their inevitable negative consequences for young children. Religious rules that demand we avoid “blasphemy,” would prevent people from interfering with the religious beliefs of others, making it harder to become alienated from their community.]

Our working hypothesis has been that during the first generations of our species, developing our ability to anticipate the future meant that we would also anticipate our own deaths. If we didn’t also evolve some way of reducing the anxiety this thought creates, the fragile sense of self in human beings would have been fragmented, [and many behaviors, essential to our survival would have lost their motivations. [Why take care of your children, if they’re only going to grow up to die? What’s the point?] Without religion, our understanding of ourselves would have been dominated by “existential” fear and anxiety, an incapacitating response that could have threatened us with extinction.

In the present epoch, most people learn at least one of these responses to the threat of personal annihilation during their childhood. Our parents, or other people who take care of us when we’re young, give us these ideas to explain how it’s possible that pets, grandparents, relatives, or friends die. The child infers that, if their grandmother’s death means that she has gone to be with Jesus, their own death will bring them the same experience, so there’s no need to be afraid. The child retains this belief as they grow up, which finds newer contexts and greater subtlety each time they go through a stage of their growth. By the time they’re adults, and able to question or challenge their own belief in God, it will have been integrated into their “default” thoughts about themselves.

We did an experiment that showed how people avoid questioning the validity of their belief in God. We saw that, even though it’s not accompanied by any psychiatric disorder, it has many of the characteristics of a delusion,. Many clinicians will recognize how difficult it can be to show a delusional patient that their beliefs aren’t reasonable. When you take such a patient one or two logical steps from seeing that their delusion is a falsehood, the patient’s thoughts often stop or they’re rerouted to another topic.

The experiment was designed to see how people steer away from concluding that one of their beliefs isn’t valid. We asked volunteers to respond to a series of connected statements that appeared for five seconds each on a computer screen. They were asked to answer yes or no as quickly as they could. The questions began by saying that the universe is made of matter and energy and gradually moved towards the development of molecules and cells. One item stated, “The neuron is a cell.” From that point on, the statements slowly moved toward a conclusion that would falsify their belief in God. The statements were:

The brain is composed of neurons.

Different interactions produce different behaviors.

All perceptions occur within the brain.

All experiences occur within the brain.

Beliefs are composed of experiences.

Most people believe in the existence of God.

God is a belief.

God is an experience within the brain.

All experiences are produced by the brain.

The experience of God is produced by the brain.

God does not exist except within the brain.

As volunteers, (especially the ones who believed in God and attended their church frequently) began to approach the statement that “God does not exist except within the brain, they took longer to give their response (even after the grammar and length of the statements were taken into account). This began around the statement that “most people believe in the existence of God”. Activity on the right side of the brain increased as they read the statements that approach the conclusion that God is generated within the brain.

This study showed us that we could perform experiments that clarify how ordinary people avoided or ignored the conclusion that their belief in God may not be valid. It also suggests that it becomes stronger each time it’s invoked and reduced someone’s anxiety. The belief appears to be a powerful mental anxiety reducer and antidepressant, which responds to challenges to the sense of self.

There is a negative aspect to this “mental opiate.” How do you respond to people believe in a different God? If their beliefs are valid, does your God lose his power and omnipotence? Suppose the God of your belief also says that he’s the only one, and those who believe differently aren’t fully human, and therefore expendable? These questions threaten the (very human) ability to believe in our own immortality, and that we will survive death. Would you kill other people in order to preserve the feeling that you’ll enjoy everlasting life, even though your body might die ?

“I would kill in God’s name”

Some disorders in the limbic system, especially the amygdala, can trigger aggressive behavior, and sometimes even result in killing other people. Stimuli that lower the threshold for activity between the amygdala and the hypothalamus (which mediates our body’s automatic controls) can occasionally evoke a violent response. The triggers can even be minor, as subtle as a specific smell, hearing a reference to a different religious belief, or a drop in melatonin levels from a geomagnetic storm.

Human beings are one of the most aggressive species that ever existed. Among mammals, we are the true Tyrannosaurus Rex. We’ve killed every kind of animal we’ve encountered, and driven many species into extinction. The human initial response to new discoveries, from stone tools to nuclear chain reactions, has been to use them to kill a perceived enemy. Since about the year 1500, around 150 million people have died in wars between nations.

It’s impossible to know how many cultures have been destroyed and pillaged in the names of Jehovah, Allah, or the creator. Although historians, anthropologists, and sociologists explain wars in terms of their political and economic origins throughout history, the individual soldiers who did the actual killing often felt that they had God’s consent. When the belief that guides you as a soldier is also the source of the promise that you’ll have eternal life, the fear of being killed in battle can seem trivial.

Even though most people would not kill anyone, even if they thought their God condoned it, the percentages of those would is disturbingly high. When first year psychology students were asked to say yes or no to the statement “if God told me to, I would kill in his name,” about 7% of them said yes. Interviews with some of the students, after they took the questionnaire, showed that they weren’t filling it out at random, or being frivolous in their answers.

25% of adult males who went to a church, synagogue, or mosque frequently said they would kill someone if they thought God wanted them to, while only 9% of the women said the same thing. Looking for predisposing factors, we found that about 50% of the men who said they would kill in God’s name also fulfilled three criteria. 1) They attended church frequently. 2) They’d had a religious experience of some kind. 3) They had higher than normal numbers of temporal lobe signs (such as déjà vu, sensing a presence, illusory sensations of movement, or chills while listening to music).

Close examinations of the personality traits and psychological tests of these people showed that they weren’t pathological. We used a very well-known psychological test, the Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory (MMPI), with questions are based on a psychiatric view of human behavior. We found that their psychiatric profiles were about average, and they certainly weren’t much different from the profiles of those who said they wouldn’t kill anyone, even if they thought their God wanted them to. When we looked specific psychological traits, like suggestibility how prone they were to imagining things, and levels of self-esteem, we found that the two groups were about the same. The people who said they would kill someone if they thought God wanted them to were, in fact, normal.

Many Scriptures, including the Bible, the Koran, the Egyptian book of the dead, the book of Mormon, the Torah, the Puranas, the Popol Vuh, and the Bhagavad-Gita, all mention killing other people as a demonstration of the god’s powers, a justification for their existence, or for their appearance on earth in human form. Those who don’t belong to a culture’s main religion are commonly marginalized as having inferior minds or emotions, and their lives are thought to matter less than those who accept it. Nomadic groups, believing themselves to be “the chosen ones”, have invaded land belonging to other nations slaughtering entire populations because they thought that God had given the land to them.

To see how normal people might agree with the idea that others should be killed when God wants it, we selected excerpts from major scriptures on this topic. We hid the source and the historical features of these religious passages, by changing some of the words, and replacing God’s name with the word “alien.” For example, one excerpt said “if you should die or be killed in the cause of the Alien, the Alien’s forgiveness and mercy would surely be better than all the riches. When you die, you will be taken by the Alien into his midst.” Another quotation read, “Those who rebel against the Alien listen to the evil forces. They become an enemy of the Alien and all that is right. Therefore the Alien has no place for them in his domain. If you die before you believe in the Alien, you will become conscious of your own guilt, which will fill your being with pain, anguish and unquenchable flames that last forever.”

We gave these items to students in the University with the title “Clinical Rating Exercise”. The students were told they were reading comments by delusional psychiatric patients about “receiving special information while they had supposedly been abducted by aliens.” The students were also told that the alien’s actual name had been changed simply to alien. Their job was to determine which of the patients were most dangerous because of their beliefs about their own death or how they saw their own mortality. The students were also told that their job was to “protect society from dangerous offenders.” The students checking the answers were asked to rate each original comment from the scriptural source (which they had been told was a psychiatric patient) on a scale between one (no danger) and seven (very dangerous).

The most obvious result from this experiment was that the students who had extreme religious beliefs didn’t think there was any danger to society in having someone believe that if they “were killed in the cause of the Alien, it’s forgiveness and mercy will be better than all the riches.” These results did not reflect any specific religion; they appeared for people of many different faiths. Rather, the results reflected the intensity, fundamentalism, or orthodoxy of their beliefs. The same subjects also said “yes” to statements like “there are things science should not investigate” or “belief in science and religion are not compatible.”

When these same statements were quoted in the original, and we revealed that the “alien” statements came from scriptural sources, they were seen as less dangerous. We don’t know if this is because today’s culture encourages respect for all religions equally, or because of the common expectation that religion can only be positive.

Implications

The outcome of our God Helmet research, as well as results from other scientists, leads us to believe that our beliefs about the gods, as well as the direct experience of their presence, and even intense epiphanies, are normal experiences, and are natural, if recondite [hard-to-accres] neural processes, and a normal brain function. Very likely, they developed in human beings along with other changes in our brains and minds that make it easier for us to adapt, survive, and achieve social success. The first role of religious beliefs could have been reducing fear of our own deaths, which if it were left unchecked, could have made it harder for us to adapt. [The various theologies and religions, including those that came later in history, may have codified socially adaptive behavior, contributing to the survival of our earliest societies, in spite of their abuse of specific individuals

There is now laboratory evidence that we can simulate the sensation of God’s presence and less commonly, visions of God. Although we have found ways of applying magnetic signals that can trigger these experiences, it seems likely that some people will need variations on the procedure in order to achieve the optimal effect. We could compare it to a clinical psychologist choosing antidepressants, and the ideal dosage for each patient. [It’s also possible that more elaborate or sophisticated stimulation procedures will allow even more robust responses.]

The brain structures that evoke the experience of God also play a role in sexual behavior and aggression. Because of this, the combination of experiences of God and certain religious beliefs can make it easy for some people to become aggressive towards those who don’t share their beliefs, especially if they believe that God had instructed them personally (a “private revelation”), [’s which can happen for some temporal lobe epileptics. Humans are a social species, and with only a few exceptions, we need to be close to others and to have a place in our social group. Unfortunately, one of the consequences of our social nature is that it can create tendency to exclude people who “don’t belong,” especially when they seem to threaten or even just disrespect the validity of the group’s beliefs.

The experiences of God that nurture religious beliefs can be provoked many ways. Some of them may still be waiting to be discovered and these discoveries could reveal phenomena even greater than the experience of God or belief in him. The idea of circles attached to other circles (“epicycles”) to explain the motion of the planets, faded away when astronomers realized the planets moved around the sun and not the earth. The idea that diseases were caused by “foul vapors” collapsed in favor of the infectious disease theory. Similarly, the belief that experiences of nonphysical beings are proof of other realms or dimensions will become superfluous. These kinds of changes have occurred all through the history of scientific discovery and advancement.

Now there is potential for a technology that could be used to amplify the experiences of nonphysical sentient beings in large numbers of people without their knowing it. The magnetic signals we’ve explored, derived from organic brain activity, could be partially broadcast over long distances. Like all technologies, it could be used for everyone, or only for the benefit of a few. This technology influences the core experiences that support the belief in immortality. Understanding the brain’s roles in the experience of God and in our religious beliefs, as well as how this compelling event it can be triggered or prevented, may be crucial for the survival of our species.

End.

♦♦♦

The Shiva Neural Stimulation System is

$649.00 Plus Shipping

(Shipping – $20.00 in the USA & $40.00 for all other countries)

ORDER THE SHIVA SYSTEM

INCLUDING THE GOD HELMET HARDWARE AND SOFTWARE

NOTE: The God Helmet is one of the Configurations for The Shiva Neural Stimulation System.

Contact us.

In the USA and Canada, you can order by calling 24/7 (Toll-Free)

(855) 408-7888

Read the Terms and Conditions before you call.

Legal: God Helmet Stimulation signals are based on the God Helmet signal templates licensed by Stan Koren and Dr. Michael A. Persinger.

The Shiva System and (it’s sibling technology), the God Helmet does not prevent, diagnose or treat any medical disorders.

The God Helmet Experiments (Book)

________

Gaia.com article on the God Helmet.

________

Review article by Dr. Michael Persinger:

Experimental simulation of the God Experience using the God Helmet

________

THE GOD HELMET is a trademark (serial number of 90072427).

.

.

.